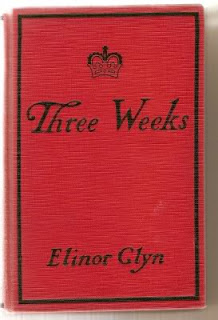

Elinor Glyn was a well-bred but rebellious English girl who grew into an envelope-pushing misfit and cultural icon. As an author, Elinor was the Jackie Collins of her day, penning erotic novels that unapologetically explored female desire. In Three Weeks, for example, she describes a sexual tryst between a very entangled couple on a tiger-skin rug. It caused quite the uproar and became the topic of many a fiery church sermon, but Glyn knew what she was doing. After releasing some sentimental romance novels that fell flat with the public, she spiced things up with a more scandalous brand of literature and coincidentally made a lot more money. She stuck to the new formula and never looked back.

Women devoured her books like chocolate-- living out their sordid and impassioned fantasies-- largely due to the fact that the heroines in Glyn's novels were never shrinking violets, but the predators of assorted male prey. This early example of female empowerment came at just the right time, as the twenties really started to roar... and the women too! As a result, the public came to depend on Elinor as a source for all things romantic, sensual, and cultured. Her built-up, exaggerated persona developed into an almost cartoonish fiction, like the Cher of the literary world, yet people identified her as a person of great class and worldliness. She took the bate, shamelessly self-promoting herself and becoming famous for her lavish wardrobe, fake eyelashes, and flame-red hair (ahem, wig). After willfully crafting herself into a social celebrity and a literary gold mine, it wasn't long before Hollywood came calling to get in on the deal.

Hollywood's poaching of this author made sense. If Glyn's saucy novels transferred to film, they were sure to reel in the big bucks. Elinor saw the possibilities as well, realizing the power that cinema celebrities would have. She correctly predicted Gloria Swanson's fate, telling her that movie stars would be considered American royalty. She encouraged Gloria to play the part, on camera as well as off, which she did. Truthfully, Glyn wanted in on Hollywood as much as it wanted her. Anita Loos herself would say, "If Hollywood hadn't existed, Elinor Glyn would have had to invent it." Referred to as "Madame Glyn" by now, Elinor ingratiated herself with all the creme de la creme. She spent time at San Simeon and Pickfair, and her declining popularity regained steam as her novels turned into films.

Her screen adaptations included the previously mentioned Three Weeks-- which was made in 1914 and again in 1924, the latter time with Eileen Pringle and Conrad Nagel-- and Beyond the Rocks, with Gloria Swanson and Rudolph Valentino, (they are pictured together in a still from the film to the right). Her stories had to be toned down a bit for the censors, of course-- it was much easier to be naughty in print-- but the melodramatic tales of forbidden, torrid romances remained. By the time pre-production started for His Hour in 1924, Elinor had enough power to refuse casting decisions on her pictures. This held great sway with the public, for if she gave a thumbs down, it meant the star was no "star" at all; if she gave a thumbs up, it meant the actor must really be something special. At first, she did not want to allow John Gilbert to take the role of Prince Gritzko in His Hour, for she had learned that he was soon to be a father (of daughter Leatrice) and found that most un-sexy. However, after meeting the charming actor, she agreed to the casting decision and was proud of his intense and sexually charged portrayal.

Her screen adaptations included the previously mentioned Three Weeks-- which was made in 1914 and again in 1924, the latter time with Eileen Pringle and Conrad Nagel-- and Beyond the Rocks, with Gloria Swanson and Rudolph Valentino, (they are pictured together in a still from the film to the right). Her stories had to be toned down a bit for the censors, of course-- it was much easier to be naughty in print-- but the melodramatic tales of forbidden, torrid romances remained. By the time pre-production started for His Hour in 1924, Elinor had enough power to refuse casting decisions on her pictures. This held great sway with the public, for if she gave a thumbs down, it meant the star was no "star" at all; if she gave a thumbs up, it meant the actor must really be something special. At first, she did not want to allow John Gilbert to take the role of Prince Gritzko in His Hour, for she had learned that he was soon to be a father (of daughter Leatrice) and found that most un-sexy. However, after meeting the charming actor, she agreed to the casting decision and was proud of his intense and sexually charged portrayal.John Gilbert and Aileen Pringle in His Hour

The studio made John take private lessons with Glyn to prepare for the role, which they were forcing many of their stars to do. Her whole persona was a ruse and she had no real knowledge of the instructions she was passing on, but poor John still had to bite his lip and sit through her tutorials on decorum and etiquette. How he kept a straight face, knowing his wicked sense of humor, is a true testament to his acting ability. Since he was still struggling at this point in his career, he probably was putting his work before his desire to guffaw. Doubtless, he had a good laugh over it later with his friends. In fact, one of his pals, Charlie Chaplin, (above) was not so inclined to play it straight. He too was forced to go in for a meeting with the Madame, but he simply started bellowing with laughter at the ludicrous situation. The miffed Glyn was beyond insulted and made no qualms about telling Charles what she thought of him. The comedian replied with a smirk: "That's too bad. I think you're a scream."

Clara Bow, oozing "it" in... It

Portrait of Glyn by Philip Alexius de Laszlo

As times changed, Elinor's themes and re-hashed storylines became old hat, as she did herself. Just as the talkies came swooping in, Glyn made her exit. She wrote a few more pieces before her death in 1943, but would never be as socially relevant as she had been during the 1920s. Her "moment" in time was interesting and perplexing, and did much to broaden the nature of fame. "Celebrity" became a title supposedly bestowed on the worthy few, as if by God himself, when in truth, celebrity was manufactured and built by the studio men. Glyn was not an exception, but the rule. She had broadcast her majesty and natural superiority to the world, yet she too was a carefully calculated contrivance. She couldn't have written herself any better. Or could she?

.jpg)

0 comments:

Post a Comment